Envisioning the East:

Russian Orientalism and the Ballet Russe

By Laurel Victoria Gray

Many of the twentieth century’s notions about Eastern dance came not from the Arab world, but from Russia. The most notable and successful exporter of pseudo-oriental dance was the Ballet Russe, the legendary company that enchanted the world with its portrayals of forbidden harems and provocative temptresses.

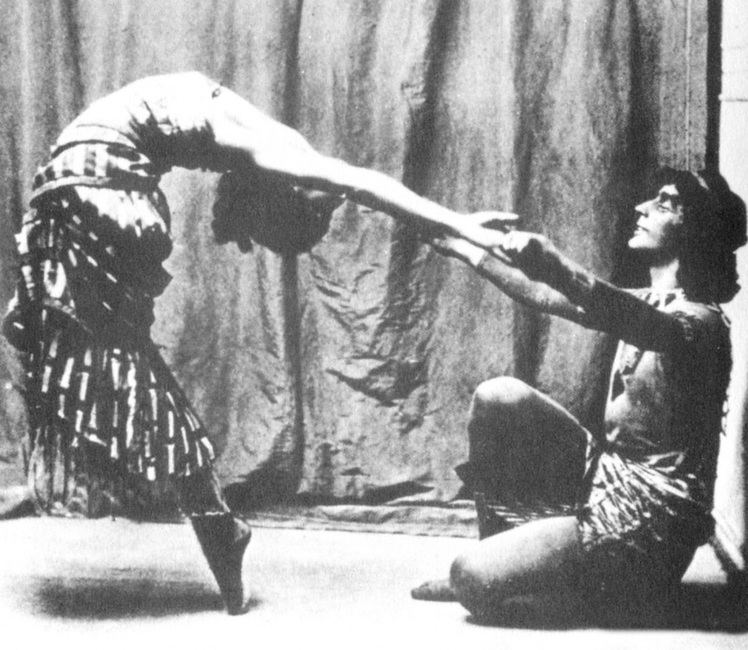

Anna Pavlova and Mikhail Fokine in Fokine’s Cléopâtra, I909

Included in the ensemble’s repertoire were the so-called “oriental ballets:”

Scheherazade, Cleopatra, Thamar, Le Dieu Bleu, Les Orientales and the

Polovestian Dances from Prince Igor. Here the genius of

Russian composers, dancers, choreographers, and theatrical designers merged to

create a dazzling vision of the exotic East, a vision so powerful that it

continues to shape popular notions about Eastern dance to the present day.1

The roots of the Ballet Russe must be sought in the Orientalist vein, which

ran through Russian literature and music of the nineteenth century, as well as

in the historical experience of the Russian people themselves. Geographical

proximity had always given the Russians exposure to Eastern peoples, although

this contact was sometimes unwilling, as in the case of the thirteenth century

Mongol invasion. As a result of the centuries spent under the Tatar yoke, Russia

was often viewed by the West as more Asiatic than European. The proverb “scratch

a Russian and find a Tatar” insinuated that beneath the Western facade lurked an

Oriental character. Clearly traditional kaftan worn by Russian noblemen and the

opulent splendor of the Kremlin interior reflected Asiatic style.

Russian literature of the early nineteenth century mirrored currents in

European writing of the period, including Romanticism. The emergence of

Romanticism brought exotic settings into vogue and “The East” became a popular

choice with many writers, artists, and musicians. But while the English and

French looked to faraway lands, such as India, Turkey, Egypt and North Africa,

Russians found inspiration quite literally in their own backyard. The East was

not a distant place, but contiguous with Russian territory. Indeed, descendants

of the Mongol hordes can be found all around, even in the best of Russian

families. Tsarist military ambitions of the early 1800s brought Russians face to

face with the fierce tribesmen of the Caucasus. Russian conquest of Central Asia

in the mid-nineteenth century added Turkestan to the empire, along the wild

nomads of the Asiatic steppe.

While the Orientalism of Western Europe often contained fantastic, invented

elements and described an East which existed only in the imagination, Russians

writers could use their first hand knowledge of the regions they described to

provide authentic detail. Tolstoy, Pushkin, and Lermontov all spent time in the

East, specifically the Caucasus. While convinced that theirs was the superior

culture, these writers admitted much that was praiseworthy of the Asiatic

peoples and admired the freedom native tribesmen — a freedom denied to Russian

intellectuals by their own repressive government.

A group of talented composers known as the moguchaia kuchka or

“mighty handful” explored Eastern coloring in their works. One trait that

distinguished Russian Orientalism in music was a sense of identification with

the East. Composers felt that to be Russian was somehow to be “Eastern” as well,

and included this in their attempt to express the Russian national character.

Not surprisingly, they attempted to capture Turkic, Persian, and Caucasian

elements in their music. The element vostochnyi—or “Eastern

element”—was first apparent in the compositions of Mikhail Glinka and was

identified by critic and scholar Vladimir Stasov. Both Stasov and Glinka

attributed this trend to the historical and cultural influences of the East on

Russia’s past. Stasov pointed to the impact of the Orient: “So much of the East

has always entered into the formulation of Russian life and all its form and has

given a peculiar, characteristic coloring.”2 Glinka felt that traces of this

influence could be distinguished in the melancholy nature of the Russian folk

song, which had somehow been transmitted though the inhabitants of the East and

their plaintive songs. As Glinka’s friend, Ivan Ekimovch Kolmakov, noted:

“Listen to the coachman along the Volga; his song is mournful, one can hear in

it the dominion of the Tatars…”3

Decades later, the Russian Orientalism of earlier generations would find new

interpretations on the concert stage. Between 1909 and 1912, the Ballet Russe

premiered six “Oriental” ballets in Paris: Polovestian Dances, Cleopatra,

Scheherazade, Les Orientales, Le Dieu Bleu, and Thamar. These

pieces depicted a wild and erotic East — passionate, sensuous, and violent. The

impact of the Eastern ballets on the Parisian public swept waves of Orientalism

throughout the world of fashion and art.

Guided by the genius of Sergei Diaghilev, the “Oriental” choreographies of

the Ballet Russe enjoyed tremendous success. With an “unparalleled ability to

orchestrate the talents of others,” Diaghilev — though neither an accomplished

artist nor dancer himself — drew the leading figures of the art world to his

banner.4 Under his direction, musicians like Igor Stravinsky and Maurice Ravel,

dancers like Vaslav Nijinsky and Anna Pavlova, and designers like Leon Bakst and

Alexander Benois, all combined their skills to create productions of singular

beauty and imagination. Not surprisingly, the music for these pieces came from

the nineteenth century Orientalist works created by composers such as Nikolai

Rimsky-Korsakov, Alexander Borodin, and Mily Balakirev. Even an Orientalist

literary work, Thamar by Mikhail Lermontov, became a spectacular vehicle for a

Ballet Russe choreography.

Music from Alexander Borodin’s opera Prince Igor inspired the

“Polovestian Dances.” The scenario for the original opera had been provided by

Vladimir Statsov in 1869.5 Borodin “imitated the folk music of the Polovstsy

after studying the Gunvalfi collection of their tunes.”6 (In the twentieth

century, Borodin’s melodies would be used as the basis for the Orientalist

musical Kismet.)

The Bakst costumes for the Polovestian Dances featured harem pants and a

nearly bare upper torso, covered only by strategically placed, pearl encrusted

hemispheres. (This was hardly the traditional clothing of nomadic tribes of the

Eurasian steppes.) Mikhail Fokine created a vivid spectacle with his

choreography. He borrowed from the dances of the Caucasus, placing long veils on

the heads of female dancers.

First the oriental slave girls undulate with their crimson and purple veils

to the languid, voluptuous tune…. After a quicker dance of wild tribesmen,

pounding timpani bring on the Khan’s warriors…who charge and leap, brandishing

their bow…The slave girls hover and at the end of their number the warriors

fling them over their shoulders.7

Cleopatra premiered in Paris on June 2, 1909, with the title role

played by Ida Rubinstein. (An earlier version had been presented at St

Petersburg’s Maryinsky Theater in 1908 with different music and set design.)

Vaslav Nijinsky and Tamara Karsavina were cast as Cleopatra’s slaves. Mikhail

Fokine and Anna Pavlova were the requisite doomed lovers — an all too ubiquitous

theme in these oriental ballets. The score combined works by various 19th

century Russian composers: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Mikhail Glinka, Sergei

Taneyev, Nikolai Cherepnin, Modest Moussorgsky, and Aleksandr Glazunov.

The staging was nothing less than spectacular, summoning the opulence and

pomp which audiences associated with the East:

A messenger announces the approach of Cleopatra. To a triumphant burst of

music a glittering procession winds to the stage.....

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT

http://thebestofhabibi.com/vol-19-no-1-feb-2002/russian-orientalism/