National Press Coverage

Scheherazade,

the great storyteller of A Thousand and One Nights, , enchanted

away thinking with her exotic tales, thus saving the lives of many innocent

women. Little did she know that one of her stories, Ali Baba and the 40 Thieves, would change another woman’s life. As

a little girl, Laurel Gray was enchanted by this Persian fairytale and was

mesmerized by the illustration of the heroine and her dagger dance. This book

was her childhood treasure. When asked to donate it to a poor family Christmas,

she succumbed, somehow knowing the story would touch her life.

The storybook

was gone, yet the magic began to weave its way into her life. Music and dance

became very important to Laurel. Her dance training began at six with ballet and

later moved to modern dance, tap, and numerous ethnic forms. Laurel’s

versatility is remarkable, ranging from Berber to Bashkir, from Slavic to

Scottish.

Music also

shaped Laurel’s artistic development. With 12 years of violin and voice

instruction, Laura was a member of the Spokane Junior Symphony and participated

in many musical and theatrical productions, giving her a solid background in

the performing arts. The creative force began to extend into costuming,

choreography, and dance research. In 1975, Laurel began her study of Oriental

dance, training with leading performers and teachers. The following year, she

joined a Middle Eastern dance troupe and began to choreograph interpretive

routines before investigating more traditional forms.

Laurel is a self-admitted

quote “ethnophile” who continually seeks out members of the local ethnic

community for advice and instruction in dance and costuming. Laurel adds. “as an outsider, I always approach a foreign culture

with respect and even awe. No matter how

much I learn, I will always be a student.” She feels that conveying the proper

demeanor in ethnic dance can be a serious challenge. “Just knowing the right

steps, wearing the proper costume, and using the appropriate music is not

enough. One must also master the feeling, and expression central to the

culture. Different societies not only dance differently, they also think differently. This can be very subtle but it is essential

to authenticity.”

This dedication

to restoring the traditional Oriental dance style was a vision outwardly

manifested in Binaat Shahrazad Folkloric Ensemble, which later became known as

the Tanavar Dance Ensemble. Like Scheherazade, her modern-day “daughters” weave

tales of faraway lands through the medium of dance. As Artistic Director, Laurel

brings this to the stage the folkloric dances of Central Asia, North Africa,

and the Middle East

Tanavar provides an outlet for Laurel’s

talents as a choreographer and teacher. She has also created a wardrobe of

authentic costumes for the ensemble through colors and textures, creating

visual pictures on stage. But she attributes Tanavar’s success to the members

of the company. Laurel comments, “The dancers have given me their time, trust,

and loyalty. They understand that

through cooperation we can create something far greater than any individual achievement.

Their nurturing support has enabled me to explore the realms of group

choreography and costuming.”

Lost

civilizations and ancient cultures have already always fascinated Laurel. She

is a trained historian currently involved in writing her doctoral dissertation.

“Performing traditional Oriental dances breathes life into the past. In the world which seems in danger of

becoming a homogeneous, it becomes crucial to preserve these unique and diverse

ethnic legacies from extinction. For example, there are no public performances

of folk dance in Iran. Through Tanavar, I hope to play a small role in keeping

dance traditions alive.”

Laurel’s efforts

have won respect of members of the Middle Eastern community. She worked closely

with the local Turks as publicist for the highly successful Turkish Festival.

The Arab community honored her by inviting her to attend a special reception

for the visiting Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia.

Ercument Kilic,

renowned teacher and performer Turkish-Azerbaijani dances recalled his

impression of Laurel, after visiting Seattle. “Her extraordinary knowledge of

the Turkic culture, history, and the spirit of this people made me more aware

of my own identity.” Reza Javaheri, an Iranian visual artist, selected Laurel to appear in a

puppet fantasy video he directed because of her mastery of Persian dance. “Her

costumes and movements were an exact replica of traditional Iranian court dances.

She has captured the essence, both musically and artistically, captivating all

with her warmth and Oriental charm.” This also explains why Laurel has become

such a popular entertainer Persian weddings and traditional celebrations. “We

are very proud of her,” adds Javaheri.

Always looking

for new challenges, Laurel is currently collaborating with Delilah, Tahia

Alibek and Hekete Balducci on a choreography entitled Phases of the Moon, Phases of the Mother, which melds Oriental

movements with modern dance. She has also been engaged by the Rubiyat Dancers

to choreograph a suite of interpretive Middle Eastern pieces for their upcoming

season. And finally, Laurel has spent the past three years developing her

original, multi-ethnic concept Dances of

the Silk Road. The project will come to fruition this year.

A friend of mine

once told me of an ancient Eastern saying, “when you are ready, the teacher

comes to you.” In 1979, Laurel began a

journey paralleling those tales spun by Scheherzade. “It was a clear case of kismet, “ she confided. While enrolled

in Russian translation course, Laurel heard about a performance by the visiting

Uzbeks. She contacted Ilse Cirtautas, a noted Turkologist, and drove off in search of these performers. When

they arrived at the hotel where the dancers were staying, Laurel noticed a

young woman in a garden near the entrance. Professor Cirtautas greeted the

stranger in Uzbek, and “her whole face lit up,” recalls Gray. “It turned out that this unassuming young

woman was none other than Kizlarkhon Dusmuhmedova, one of Uzbekistan’s most

famous dancers.

That same evening Laurel watched the Dancers

Members of the Bakhor Ensemble performed. She was entranced. “To me, this was

true Oriental dance – feminine, graceful, playful, and dramatic.The costumes

were modest, but sumptuous and colorful. One dance, called Munadzhat or “suffering,”* struck Laurel. Entranced by its rare

beauty, she asked Kizlarkhon to teach it to her. She taught the dance to Laurel,

telling her that very few had mastered the choreography since it requires a

high level of technique, and a great deal of expressiveness.

Although she has

performed Munadzhat on several occasions,

she claims modestly that she has yet to master it, Munadzhat

is very demanding, very deep. I could spend the rest of my career perfecting

it.” But as someone who has seen Laurel’s

Interpretation of this classical piece, it is both moving and inspiring. With her grace and vitality, she brings to

life the frozen sculptures of the past.

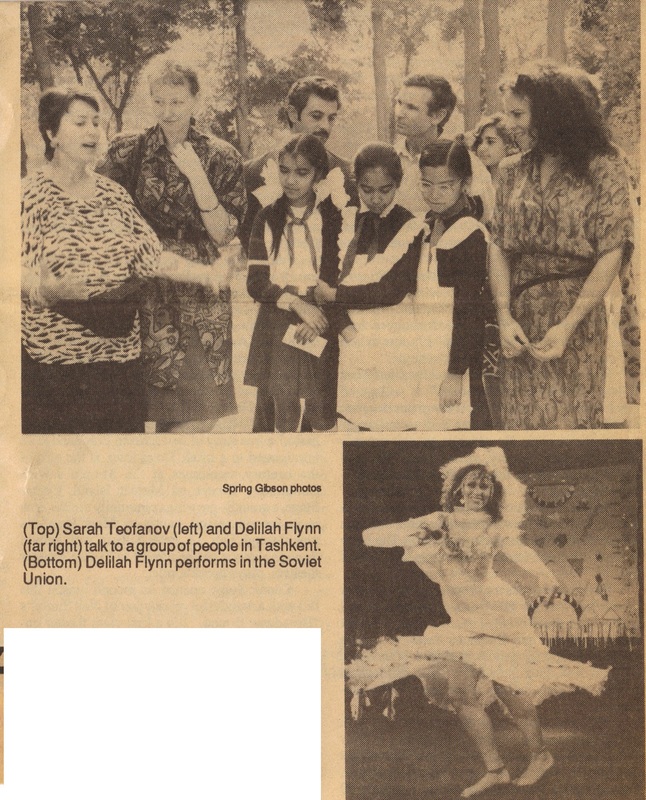

Regardless of

Laurel’s of self-evaluation, the visiting Uzbeks were quite taken with her and

her dances. The Deputy Mayor of

Tashkent, Sabir Yusupov, mistook her ensemble for Uzbeks when they appeared on

stage. He was very impressed with Laurel’s talent and sincere interest in Uzbek

culture and felt that, if she lived in Uzbekistan, she would have been granted

the title “Honored Artist,” and her dance company would have been funded by the

State.

This was only

the beginning of Laurel’s dream -, which she had first visited in to return to

Tashkent which she first visited in 1973. The dream became a reality through

the efforts of her colleagues, friends, and admirers.

Special benefits

were held, including one at the home of the Mayor of Seattle, Charles Royer,

and his wife Rosanne. Laurel is held in such high esteem by her peers that they

were willing to provide the financial assistance necessary for her to serve as

a member of the official delegation. [The

dancer]Morocco states it succinctly: “I first saw her over five years ago and

was impressed by her seriousness, sincerity, quality, class, and talent. The

longer I know her, the longer the above impressions become. She’s one of the

people who make all the work, caring, concern and hassles worth it. She makes

me glad I’m a dancer and I care.”

All Laurel’s efforts

were rewarded when she lnded in Leningrad

in September of 1984. In those those euphoris weeks, we was often moved to

tears of the intensity of her experiences. She visted museums, art galleries, theatre

performances of State ensembles and met dignitaries – from dancers to legendary

figures. One such heroine in Tashkent was Tamara Khanum, Uzbekistan’s original

feminist. “Now 80, Tamara Khanum dared to dance in public. She cast aside her

veil and grasped new found freedome to perform her art in public.” After receiving

Laurel in her home, Tamara Khanum presented her with several gifts, including a

scarf awarded for valor, and praised her dancing. When she learned of Laurel’s

efforts to promote Uzbek dance through Tanavar and without government support,

she exclaimed “Molodyets [wonderful

girl], you are a heroine. Indeed, it

must have seemed surprising to watch the cavorting of red-haired American guest

in a long denim skirt as she spun and

executed traditional movements with the subtle grace of a native.

Galia Ismailova,

an Uzbek dancer who has earned the coveted title of People’s Artist was quite impressed with the depth of Laurel’s

knowledge and the nature of her questions. Madame Ismailova playfully remarked,

“Who is teaching whom? You already know

everything about our dances.”

On several

occasions, Laurel was asked to dance by herself or with leading dancers. Drawing

upon every drop of training in music and dance – and feeling that national

honor was at stake – she reluctantly agreed. To the amazement of her dancing

partners and the musicians, Laurel follow flawlessly. “You have captured every

subtlety, every characteristic of our dance,” remarked the Mayor of Tashkent. Remembering

the impromptu duet she performed with a professional Uzbek dancer, Laurel

recalled, “It was an icon to true friendship, to true understanding between

peoples. Politics melted into insignificance. We were only two dancers and time

stood still”

To be accepted

as an Uzbechka (an Uzbek woman) by

the natives was truly a remarkable accomplishment, and Laurel was to receive an

honor beyond any dancer’s imagination. During

an official banquet musicians began to play a song. To Laurel’s amazement, what

they played was Tanavar. The Uzbeks

were quite familiar and excited about Laurel’s dance company named Tanavar and honored her by dedicating

the song to her. “So I danced”, she recalled, “aware only of the music and the

happiness of the dream fulfilled.” A measure of her success was evidenced by the November 30,

1984, article in the newspaper publication Pravda

Vostoka, praising Lolakhon (as

Laurel was then nicknamed by the Uzbeks) and stating that she had quite

literally created a furor with her splendid performance” at a folk concert.

Laurel has been

sought out for consultation and instruction by dancers nationwide. Minnesota’s

Ethnic Dance Theater comissioned Laurel to set as the choreography for the

company’s Central Asian suite.

Being a published

author herself, Laurel enlightens us through articles in Arabesque, Habibi, Fantasia, Viltis, The Northwest Folkdancer, Caravans, Middle Eastern Dancer, Ethnic Arts Quarterly and Jareeda. She enjoys doing historical

research and finds it rewarding to share her findings with others. “Writing is

so different from performing. When you dance, the response is immediate, but

when you write you never really know whether you’ve touched someone. Sending

off an article can be a lonely experience. The mailbox might as well be a ‘black

hole.’ That is why I’m so touched when someone says ‘I liked your article.’”

Laurel has established herself as a serious writer of the first rank. Magda

Barron, former editor of Arabesque recalled

to me, “I’m delighted every time one of her articles arrive in the morning mail

– and it makes my day. I can always count on Miss Gray to produce an impeccably

researched and supremely intelligently written piece. It is rare indeed to find

a writer who is so consistent and informative, not to mention prolific.”

I was one of

those readers who, in the midst of becoming an Uzbekophile, wrote to Laurel to

tell her that I liked her articles. She immediately began to share with me all

her painstakingly gleaned information: costumes, videos, books, records and

artifacts. Her generosity and expertise opened the door to my personal quest in

Uzbek dance. For those interested in Turkic, Persian, and Arabic dance

traditions, a visit Seattle has almost become a mandatory pilgrimage. I made such a trip and the result was a deep

and genuine friendship.

During a bout

with cancer last March, I learned the value of our friendship. Laurel began an underground

movement to help me fight his illness. She spent hours contacting my colleagues

and friends around the country explaining my crisis and asking them to help, I

was inundated with inspirational letters and cards wishing me a speedy

recovery, not to mention a letter hope daily from Laurel. Her compassionate nature and sense of humor,

provided me with the necessary fuel to fight my illness and eventually win.

Being in dance

for over 10 years, I have seen the gamut of professional and amateur artists. Our profession can only flourish by those who

give selflessly to their art. Laurel is such an example. She approaches her art

as a true professional. She has it an honest desire to share it, enough respect

to do the necessary homework to improve it, and enough faith to let go once it

is created. It is not exaggeration to denote her as the pioneer of Uzbek dance in America never trying to popularize the

genre at the cost and genuineness. As Scheherazade became a heroine of One Thousand and One Nights, Laurel in

her way has become a modern-day heroine. She has rescued Uzbek dance from

obscurity and earned for it a rightful place in the dance world.

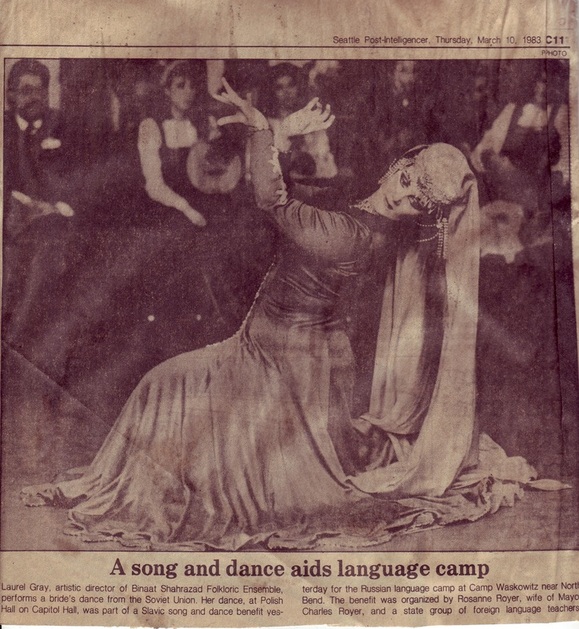

A Song and Dance Aids Language Camp

Seatle Post Intelligencer

March 10, 1983

Laurel Gray, Artistic Director of Binaat Sharazad Folkloric Ensemble , performs a bride's dance from the Soviet Union.

Laurel Victoria Gray's Persian Dance

Choreographies featured on Iranian.com

PHOTO ESSAY

BY OMID ALAVI

Silk Road Dance Company's annual Nowruz Concert

at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

http://www.iranian.com/Diaspora/2007/April/Phil/index.html

BY OMID ALAVI

Silk Road Dance Company's annual Nowruz Concert

at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

http://www.iranian.com/Diaspora/2007/April/Phil/index.html

"Egypta" Reviewed By Washington Post

Silk Road Dance Company

Ancient Egypt came alive Saturday night at Dance Place with the Silk Road Dance Company performing Laurel Victoria Gray's

evening-length "Egypta: Myth, Magic & Mystery." With the passion of an educator and avid storyteller, Gray, along with her 23-member troupe, proceeded to unfold the myths and history of the ancient world. The work is a "reconstruction of what they might have danced like," said Gray, who drew her ideas from ancient Egyptian art as well as current Middle Eastern dance styles.

Originally a tribute to the early 20th-century modern dancer Ruth St. Denis, it evoked the dramatic gestures of silent films. A colorful whirl of motion connected a series of recognizable Egyptian tableaux (at times perhaps too recognizable, verging on cliche). A deep voice coming from a smoky netherworld narrated the historical dance-drama replete with striking and sumptuous images: A quartet of glistening aqua nymphs emerged from the Nile, depicted by billowing silk. Thoth, the alligator god and creator of life, made his way across the floor swishing a magnificent gold-and-blue brocade tail. The costumes, designed by Gray and Elizabeth Anna Groth, were scene stealers.

Mythic dances were interspersed with ones depicting the everyday lives of people in the kingdom. Women shown harvesting in a ritual dance had a distinctly African flavor, and linen weavers, working at the loom with playful gestures, framed the myths nicely.

The evening was a visual treat of whirling, glittery costumes, fluid movement narratives, rich, exotic music and a dance troupe that was clearly having fun.

Barbara Allen

© 2004 The Washington Post Company

Ancient Egypt came alive Saturday night at Dance Place with the Silk Road Dance Company performing Laurel Victoria Gray's

evening-length "Egypta: Myth, Magic & Mystery." With the passion of an educator and avid storyteller, Gray, along with her 23-member troupe, proceeded to unfold the myths and history of the ancient world. The work is a "reconstruction of what they might have danced like," said Gray, who drew her ideas from ancient Egyptian art as well as current Middle Eastern dance styles.

Originally a tribute to the early 20th-century modern dancer Ruth St. Denis, it evoked the dramatic gestures of silent films. A colorful whirl of motion connected a series of recognizable Egyptian tableaux (at times perhaps too recognizable, verging on cliche). A deep voice coming from a smoky netherworld narrated the historical dance-drama replete with striking and sumptuous images: A quartet of glistening aqua nymphs emerged from the Nile, depicted by billowing silk. Thoth, the alligator god and creator of life, made his way across the floor swishing a magnificent gold-and-blue brocade tail. The costumes, designed by Gray and Elizabeth Anna Groth, were scene stealers.

Mythic dances were interspersed with ones depicting the everyday lives of people in the kingdom. Women shown harvesting in a ritual dance had a distinctly African flavor, and linen weavers, working at the loom with playful gestures, framed the myths nicely.

The evening was a visual treat of whirling, glittery costumes, fluid movement narratives, rich, exotic music and a dance troupe that was clearly having fun.

Barbara Allen

© 2004 The Washington Post Company

'Thank you' tea will mark end of journey for performance group

The North Seattle Press February 7 - 20, 1990. page 6

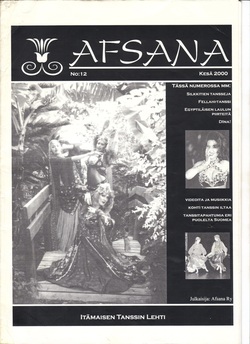

Laurel Victoria Gray on cover of Afsana Finnish Dance Magazine

June 2000

DANCE WORKSHOP REVIEW

Laurel Gray in Washington DC

reviewed by Elizabeth Mourat

Middle Eastern Magazine

volume 9, number 7 APRIL 1988

After attending many dozens of semars, I have come to accept that the most we can hope to retain is a few steps, some information and a part of the essence of the teacher. Years go by and the choreographies are long gone from our minds, but the essence of the teacher should remain. And while dancing, if one thins of that teacher, it is possible to almost experience that essence. Such will be the case when I recall the Laurel gray workshop, sponsored by Bedia, that I attended in Washington DC.

I knew I was in for a treat because I had read some of Laurel's writings and her reputation favorable preceded her. What I was not expecting was the sheer power and command of this woman, yet she was not overbearing or intimidating. She was generous and gentle. Laurel is a perfectionist and an incredibly competent instructor.

After two very special days with her, we were all somehow inspired to go beyond the steps and beyond the information. We felt a reverence and deep respect for the dances we learned, the people they came from and the teacher who taught us. The historic information Laurel gave was impeccable.

The steps were clearly and simply broken down. Her approach to teaching was systematic and this made it easier for us to retain the materials that she so unselfishly shared. The steps were codified with numbers and image producing names. For example, sixth position Classical Persian looks somewhat like a woman making an offering. There were also handouts and illustrations. We also saw two videos that were invaluable in illustrating these dances.

What is it about this woman that makes her so different? We were frequently given one-on-one attention. We could not help but trust this calm and communicative teacher with penetrating eyes. She said she was not a "hit and run" teacher; we were to know she is the kind of instructor who would remember our names and even answer our letters.

She bonded herself with the women in the class in more ways than one. Her opening statement concerning the Uzbek dances was that women had been put to death as a result of doing these dances. She put us on our honor to not abuse these dances.

It was clear her mission is to preserve, resurrect and protect the dances that are so precious to her, I wonder how the Middle Eastern dances we so often see performed today would look if there had been this steadfast safeguarding in the early years.

The study of Uzbek dance was a new experience for most of us. The video. "Dances of the Silk Road." produced by Laurel (See Middle Eastern Dancer, Nov. 1987 issue for review) was informative and entertaining. As a visual aid, it was an interesting vehicle for teaching the history and culture of the Uzbek people. This, I feel, is an essential part of learning a "foreign" dance. Otherwise, we find ourselves doing shallow renditions of what I call "orphan dances." There is no depth, no substance, no lineage -- just fluff -- and not very good fluff at that. You know the type of class where all you get is technique with no reference to roots -- "...a shimmy shimmy pop and a hip to the left and a hip to the right and a smile so cure and a rib shift right and a left right left...etc." You walk away wondering what you just did and invariably forget it all. Laurel reminded us repeatedly how cultures shapes dance. We flt new understanding and compassion for these remote people who most of us had barely heard of before.

The Classical Persian workshop was delightful. Laurel performed a mime sequence that was absolutely spellbinding. In an instant, her emotions flashed from gaiety to fear to pride to anger and she carried us right along with her. Throughout this improvisational piece, she wore a mask, communicating all of these images with only her body. Yet beneath the mask, we could see her eyes blazing. She was someone else with each change. It was breath-taking.

We then had an opportunity to try our own "hand" at this art as we applied imaginary make-up to ourselves. This exercise was to illustrate the mimetic aspects of Persian dance. Our individual make-up sequences were later added to the Classical Persian choreography. This piece was lyrical and moving. We painted pictures with our poses. The postures were directly taken from antique miniature paintings and other works of Persian art. Her choreography followed logically and skillfully balanced different speeds, levels, and moods. We had just enough repetition and time with this choreography to be able to work on it at home.

The videos of the Persian dances were exciting and revealed a great deal to us about the courage and grace of these dancers. Laurel's example, her exercises and her anecdotes impressed upon us the essence of this lyrical and fluid art. We also developed a deep concern for the plight of the Persian dancers __ many of whom are in grave danger. Classical Persian dance is an elegant form of poetry in motion and how valuable for us to have people who can pass this on to the new generations. In these tragic times for Iran, there is the very real danger that these exquisite antique dances may be lost forever. This could be likened to deforesting a magnificent primeval mountain. Should that unforgivable day ever come, I feel confident that Laurel will be wandering over the hill defiantly planting her seeds. The dances will not be lost as long as there is breath in her body.

It was clear her mission is to preserve, resurrect and protect the dances that are so precious to her, I wonder how the Middle Eastern dances we so often see performed today would look if there had been this steadfast safeguarding in the early years.

The study of Uzbek dance was a new experience for most of us. The video. "Dances of the Silk Road." produced by Laurel (See Middle Eastern Dancer, Nov. 1987 issue for review) was informative and entertaining. As a visual aid, it was an interesting vehicle for teaching the history and culture of the Uzbek people. This, I feel, is an essential part of learning a "foreign" dance. Otherwise, we find ourselves doing shallow renditions of what I call "orphan dances." There is no depth, no substance, no lineage -- just fluff -- and not very good fluff at that. You know the type of class where all you get is technique with no reference to roots -- "...a shimmy shimmy pop and a hip to the left and a hip to the right and a smile so cure and a rib shift right and a left right left...etc." You walk away wondering what you just did and invariably forget it all. Laurel reminded us repeatedly how cultures shapes dance. We flt new understanding and compassion for these remote people who most of us had barely heard of before.

The Classical Persian workshop was delightful. Laurel performed a mime sequence that was absolutely spellbinding. In an instant, her emotions flashed from gaiety to fear to pride to anger and she carried us right along with her. Throughout this improvisational piece, she wore a mask, communicating all of these images with only her body. Yet beneath the mask, we could see her eyes blazing. She was someone else with each change. It was breath-taking.

We then had an opportunity to try our own "hand" at this art as we applied imaginary make-up to ourselves. This exercise was to illustrate the mimetic aspects of Persian dance. Our individual make-up sequences were later added to the Classical Persian choreography. This piece was lyrical and moving. We painted pictures with our poses. The postures were directly taken from antique miniature paintings and other works of Persian art. Her choreography followed logically and skillfully balanced different speeds, levels, and moods. We had just enough repetition and time with this choreography to be able to work on it at home.

The videos of the Persian dances were exciting and revealed a great deal to us about the courage and grace of these dancers. Laurel's example, her exercises and her anecdotes impressed upon us the essence of this lyrical and fluid art. We also developed a deep concern for the plight of the Persian dancers __ many of whom are in grave danger. Classical Persian dance is an elegant form of poetry in motion and how valuable for us to have people who can pass this on to the new generations. In these tragic times for Iran, there is the very real danger that these exquisite antique dances may be lost forever. This could be likened to deforesting a magnificent primeval mountain. Should that unforgivable day ever come, I feel confident that Laurel will be wandering over the hill defiantly planting her seeds. The dances will not be lost as long as there is breath in her body.